Assessing Inventive Step of patent applications using

a multicriteria index: An empirical validation.

Fritz Dolder [1], Christoph Ann [2] and Mauro Buser [3]

Cite as: Dolder F., Ann C., & Buser M.,

"Assessing Inventive Step of patent applications using a

multicriteria index: An empirical validation.", In European

Journal of Law and Technology, Vol 5., No. 1., 2014.

Abstract

Inventive step constitutes the condition for

patentability of inventions most difficult to determine (Art. 56

EPC). The assessment is currently performed by the Boards of

Appeal of EPO without pre-determined and structured procedures

and usually results in one-reason decisions. To improve the

reproducibility of the assessment a multicriteria index ISPI

(Inventive Step Perception Index) was applied accumulating the

reasoning of past decisions of the Appeal Boards of EPO. The

present investigation was performed in order to validate this

instrument and to compare the results obtained with the results

of one-reason decisions.

Empirical work was staged on two test cases

decided in the past by two different Appeal Boards of EPO. One of

them was positive (grant of the patent), the other was negative

with regard to inventive step (revocation of the patent). Large

samples of students (each about N = 200) were called to assess

inventive step in these two cases with either the support of the

ISPI index, or with the usual unstructured procedures (control

group).

The reproducibility of the assessment was judged

by calculating inter-rater concordance of the results using

Cronbach's Alpha (target value: > 0.9), their inter-criteria

concordance (target value: < 0.3); hence it is suggested that

in an efficient assessment tool the targeted ratio between the

two values should be below < 0.5.

A consistent cut-off value of the cumulated ISPI

score was selected by the ideal observer's view, minimising false

results (mis-classifications) as compared to the decision of the

Appeal Boards. By using this selected cut-off value the rate of

mis-classifications could be significantly reduced (37.81%, 25.00

% respectively) as compared to the rate obtained by evaluating

the identical set of facts with unstructured holistic procedures

(65.61 %).

Our findings are consistent with findings of

Arkes et al (2010) and (2006) showing that multicriteria

assessments offer advantages against one-reason decisions. The

results are explained in part by the fact that applying ISPI

creates a consistent constraint for completeness of assessment

for the decision-maker, while such a constraint is not felt when

unstructured procedures are used in one-reason decisions.

The empirically validated index will prove useful not only in

patent prosecution and patent litigation, but also in valuing

patent assets in a business context.

1. Introduction

Decisions in different areas of law are based on

the assessment of performance or quality of complicated

technological, scientific, medical, or social phenomena on the

background of a statutory term all to often defined in a general,

and hence vague form. This assessment can be performed either by

holistic (one-reason) or by multicriteria procedures. Since

holistic assessing is based on or at least linked to an overall

impression incorporating almost necessarily subjective and

irrational elements, it leads more or less inevitably to

one-reason decisions selecting one decisive attribute of the

object, or one criterion of assessing. A serious drawback of this

procedures consists in that raters may find it easier to slip

illegitimate, or irrelevant but appealing criteria into their

ratings when using such unstructured holistic procedures

(Arkes et al. 2010, 265).

Multicriteria heuristics, on the other hand, is

based on a predetermined algorithm of steps: Defining and

selecting a plurality of relevant attributes and criteria of the

phenomenon to be assessed, attributing relative weights to the

criteria, setting scales for assessing the criteria, assessing

the score of each of the relevant criteria and aggregating the

scores of the individual criteria into a multicriteria score of

the object to be assessed. This multicriteria procedure requires

predetermined framework comprising definitions of the presumably

relevant criteria, their relative weight and scales, and a

mechanism by which the scores of the individual criteria are

aggregated into a final over-all score of the phenomenon to be

qualified.

The superiority of systematic multicriteria over

one-reason holistic heuristics has been established in a variety

of areas and for a variety of different tasks other than legal

decision making (Ravinder et al. 1991, Ravinder

1992, Arkes et al. 2006, Arkes et al., 2010,

Zopounidis & Doumpos 2002). However, evidence for a

number of practical advantages of one-reason heuristics in areas

other than legal decision making have been equally reported.

(Gigerenzer 2007, Rieskamp et al. 1999)

Inventive step constitutes the condition for

patentability of inventions most difficult to determine (Art. 56

EPC). The assessment is currently performed by the Technical

Boards of Appeal (TBA) of EPO without pre-determined and

structured procedures and usually results in one-reason

decisions. To improve the reproducibility of the assessment a

multicriteria index ISPI (Inventive Step Perception Index) was

proposed accumulating the reasoning of past decisions of the

Appeal Boards of EPO. The purpose of the present study is to

validate empirically the different features of this multicriteria

index ISPI within the legal framework of the European Patent

Convention (EPC). In order to validate this index and to compare

the results obtained with the results of the one-reason decisions

an empirical investigation was performed by experimental

assessments of selected TBA test cases by large samples of

student raters.

2. Assessing inventive step by

one-reason-decisions

2.1 Inventive Step (Non-obvious Subject Matter, Non-obviousness)

Inventive step (non-obvious subject matter,

non-obviousness) has been considered for decades to be the

requirement of patentability of inventions which is by far the

most difficult to evaluate and to yield results which are safely

reproduced from one decision-maker to another.

Art. 56 EPC: An invention shall be considered as involving

an inventive step if, having regard to the state of the art, it

is not obvious to a person skilled in the art. (....)

The applicable statute does in wording not provide efficient

and detailed guidance with regard to the procedures and methods

to be applied for decision making in individual cases. The

Guidelines for Examination of EPO although

containing a catalogue of relevant (and apparently: independent)

criteria (Part G- Chapter VII) are conceived apparently on the

paradigm of the one-reason-decision. Therefore, they do not offer

a consistent algorithm for taking into account all criteria which

might be (equally and simultaneously) relevant in a given case

and for aggregating the scores of such different criteria: The

examples relating to the requirement of inventive step in

Guidelines EPO June 2012, Part G - Chapter VII-13 Annex-

indicators are indicated here together with the code of the

corresponding criteria of ISPI (see infra Section

2):

- Application of known measures (F2)

- Obvious combination of features (P 21.2)

- Obvious selection (P 25)

- Overcoming a technical prejudice ( A 42)

Therefore, decision making on inventive step is

currently achieved in most cases of the TBA through holistic

procedures based on implicit preferences of the decision-makers

and regularly result in one-reason-decisions: The rater

selects one single attribute of the patent application to be

assessed and applies one single criterion for assessing this

attribute thereby implicitly avoiding all other, perhaps equally

and simultaneously relevant criteria. In the following examples

of typical reasoning of Technical Appeal Boards of EPO the

decision was exclusively based on one single independent

criterion.

TBA 1199/08 of May 3, 2012.

No. 38. The only difference between the sperm

sample of claim 14 and the one of document D30 lies in the use of

an extender comprising Tris, whereas in document D30 the extender

consists of a combination of egg yolk and citrate of sodium.

(....)

No. 40. Appellant I argued that a skilled

person would have been discouraged to replace the egg

yolk/citrate sodium extender of document D30 by a Tris-based

extender (....)

No. 41. Thus, the skilled person looking for

an alternative for the egg yolk / citrate of sodium extender used

in document D30, (....), would have had no reason to ignore the

teaching in document D5. By exchanging the extender disclosed in

the closest prior art by one of the extenders disclosed in

document D5 as being known to be useful for freezing of bovine

sperm he/she would have arrived at the subject-matter of claim 14

in an obvious manner.

No. 42. Thus, the Board decides that the

subject-matter of claim 14 does not involve an inventive step and

that the main request does not comply with the requirements of

Article 56 EPC.

The decisive criterion applied in this case

consisted of whether a technical prejudice

existed among the skilled workers against transferring

knowledge of a given document of the state of the art to the

patent application in suit (reasoning under Guidelines EPO G-VII-

Annex 4, see item # A42 of ISPI, infra 2.2):

TBA 1616/08 - Gift order/AMAZON of November 11, 2009, No.

9.

The mere wish to automate process steps that

have previously been performed manually is usually regarded as

obvious. The automation details may naturally be inventive, but

in the present case the problem of how to extract the delivery

information is left entirely to the skilled person. Thus an

inventive step is neither involved in the idea to extract

information automatically, nor in its implementation. The

subjectmatter of claim 1 is therefore obvious.

In this case the decisive criterion was the

classification of the invention into the category (mere)

automation of a process which had been previously performed

manually (corresponding to code T 33.1 of ISPI).

From the Decision of the Opposition Division in

continuation of case of TBA 1616/08 - Gift order/ AMAZON of June

21, 2013:

Claim 1 of the third auxiliary request is

based on two different groups of features.

a) the features of claim 1 of the second

auxiliary request and

b) a selection of the features of the

single-action ordering to the main request discussed in T

1244/07.

The opposition division does not see any kind

of technical interaction between these two sets of features, they

are therefore, in the view of the Opposition Division, just

aggregated. According to the practice of the EPO the mere

aggregation of non inventive subject-matter cannot involve an

inventive step. [....] During the oral proceedings, the patentee

agreed that indeed claim 1 can be divided in the two above

defined set of features but was of the opinion that a synergetic

effect had to be acknowledged in the claimed combination.

[....]

The opposition division cannot follow that

argumentation because it is not possible to recognise any new

technical effect (i.e. an effect which is not present when either

one or the other of the two sets of features is used) resulting

from the claimed combination. In conclusion, the Opposition

Division, in view of the above cited decisions of the Board, is

of the opinion that the subject-matter of claim 1 of the third

auxiliary request does not fulfil the requirements of Art. 56 EPC

because it is a mere aggregation on non inventive features.

[....]

In this case the decision was based again exclusively on one

single criterion, namely the famous aggregation - combination

issue as advised by Guidelines EPO G-VII- Annex 4, see code P

21.2 of ISPI:

2. Obvious combination of features? 2.1

Obvious and consequently non-inventive combination of features:

The invention consists merely in the juxtaposition or association

of known devices or processes functioning in their normal way and

not producing any non-obvious working

inter-relationship.

2.2 Poor Reproducibility of One-Reason Decisions

In view of this widespread one-reason mechanism

it is not surprising that poor reproducibility of the results of

assessment of inventive step is accepted in the patent community

to constitute a central problem and one of the main difficulties

of patent prosecution & litigation since the development of

inventive step into a statutory requirement of patentability in

the early 20th century. Within the context of EPO prosecution,

this is evidenced in part by the remarkably high percentage of

cases which are reversed by the TBAs (assuming that the TBA

decisions are in their overwhelming majority (90 % ?) based on an

assessment of inventive step differing from that of the

examination, or opposition divisions):

European Patent Office 2009, Annual

Report : Cases settled by TBAs in 2009: 1918, allowed (in

part) 740 (38.6 %), dismissed 589, otherwise

(e.g. withdrawal) 589; based on opposition procedures

(inter-partes): cases settled 1116, allowed (in part) 508

(45.5 %), dismissed 337, other 271 (page 41).

Opposition procedures: Patent revoked 43.6 %,

patent maintained in amended form 30.1 %, opposition rejected

26.3 % (page 19).

In the course of our investigation this

relatively poor reproducibility of inventive step assessment was

evidenced by the fact that two test cases could easily be found

which had been both reversed by their respective TBAs (see

infra Section 3.1).

Recent opinions of eminent experts of the US

patent community have not unexpectedly confirmed this current

state of poor reproducibility of decisions on inventive step. As

was stated by U.S. federal appellate judge Richard A.

Posner in NYT International Weekly of 15th October

2012 (Duhigg / Lohr 2012):

"There's a real chaos. The standards

for granting patents are too loose."

And in the same issue of NYT another U.S. patent

expert, Raymond Persino, a patent attorney who had

previously worked as an examiner, was reported to state:

"If you give the same application to 10 different

examiners, you will get 10 different results"

2.3 Person Skilled in the Art and Other Formulae

The notional person skilled in the art

(Durchschnittsfachmann) has contributed little to improve

this unsatisfactory situation: Although this fictitious person is

still mentioned in the Guidelines (June 2012 Part G - Chapter

VII-3 and 3.1 ) it has never been disputed that art. 56 EPC (and

its equivalents in the national statutes) does not address the

layman in the street who will not even understand semantically

patent documents. Furthermore, it was never disputed that the

standards for evaluation of inventive step should be set by the

expert knowledge available in the relevant scientific

specialities. Thus, although being currently mentioned in

decisions of the TBAs the person skilled in the art

proved to be of modest cognitive value so far and was

not able to steer decision making under art. 56 EPC to a

significant extent.

Other notional formulae or tests

proposed under art. 56 EPC are of equally modest cognitive value

and have made equally small contributions in improving the

inter-personal reproducibility of decisions. The following two

formulae both appeal to the subjective personal perception of the

decision maker with regard to the probability of success in a

given technical context and can as such not be expected

to improve the inter-personal reproducibility of decisions

significantly:

Could - would approach (Guidelines June 2012,

Part G-Chapter VII-5.3): This notional test is based on the

reasoning that "the point is not whether the skilled person

could have arrived at the invention by adapting or

modifying the closest prior art, but whether he would

have done so because the prior art incited him to do so". The

difficulties in using this test in a reproducible way are

evidenced by the statement that:

"even an implicit prompting or

implicitly recognisable incentive is sufficient to show that the

skilled person would have combined the elements from the prior

art (see T 257/98 and T 35/04)".

This notional test was invented in a patent

litigation in 1928 by Sir Stafford Cripps, K.C., in Sharp &

Dohme Inc. v. Boots Pure Drugs Company Ltd. [1928] 45 R.P.C. 153,

Court of Appeal (CA) March 9, 1928 (Bryant,

1997, p. 60-62) and this test had an unexpected

renaissance after the EPO started examination of patent

applications in 1978.

The contrast between reasonable expectation of

success (angemessenen und realistischen

Erfolgserwartung) and mere hope of achievement (blosse Hoffnung

auf gutes Gelingen) is equally praised to be a valuable

instrument for making decisions under art. 56 EPC: T 296/93 and T

207/94. But this notional contrast is merely a verbal expression

of the probability of success as subjectively perceived by the

decision maker. As ruled in T 207/94 the hope of achievement

expresses a desire, while the expectation of success requires a

scientific evaluation of the facts in a specific case.

As a contrast to such sophisticated, but not

really helpful legal semantics it should be realistically

acknowledged that practical legal decision-making under art. 56

EPC is based more or less implicitly on the simple understanding

that to be inventive a technical performance has to be more than

average in a specific technical context.

3. The Multicriteria Index ISPI

The multicriteria Index ISPI (Inventive Step

Perception Index) for assessing inventive step of inventions was

proposed to provide the decision-maker with a structured

instrument for the various criteria of assessment in view of

improving the reproducibility and accuracy of assessing inventive

quality (Dolder 2003). ISPI applies the

classical procedure of Simple Additive Weighting (SAW), which is

probably the most widely used MCDA method, but in the present

context has the great advantage to be easily understood by the

non- statistician, i.e. patent practitioners. This linear

weighted sum:

V(x) = Σ wi vi (xi)

was assumed to provide a good overall measure of

inventive performance (xi: single attributes /

criteria, wi : weights, and vi: value

functions), particularly since it allows compensation, i.e. the

assessed patent application may compensate poor scores on a

particular criterion x1 by better scores on other

criteria xn.

3.1 Selecting attributes and

criteria

Since ISPI was conceived to continue the

experience and standards of past EPO case law, the authors of

ISPI were not free in their choice of criteria, but rather bound

to the lines of argumentation of past TBA decisions. Therefore,

ISPI criteria were selected exclusively from

patterns of reasoning found in the past decisions

of the TBAs and, to a some extent, in the Guidelines for

Examination 2012 of EPO. ISPI therefore assesses inventive step

exclusively

on the basis of criteria which were previously

held to be relevant in the past reasoning of EPO. The mere fact

that a criterion was applied in the reasoning of the TBAs (at

least once) was the only condition for admitting the criterion

into the catalogue of ISPI index.

With regard to the number of criteria, it is

commonly accepted that the risk of confounding, i.e. yielding

higher scores than could be expected statistically from

independent attributes increases with increasing number of

attributes. This results in the same attribute being implicitly

assessed more than once, therefore being implicitly

over-weighted. Since the criteria applied should be as

independent as possible from each other, the number of criteria

was restricted to the minimum required by the past TBA case law

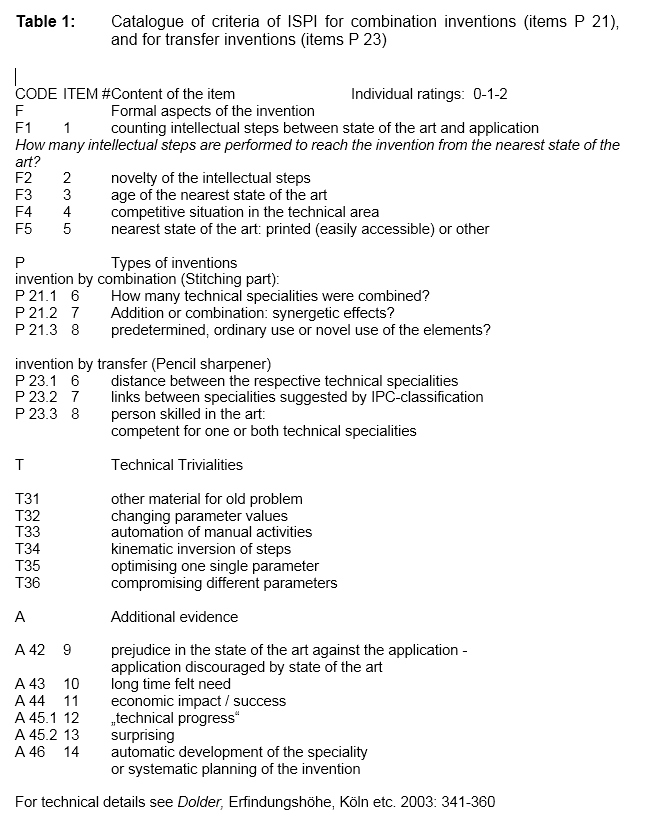

providing input in this respect (i.e. group F = 5 criteria, P =

3, T = 2, A = 6, total of 14 criteria, and if group T applies, to

a total of 16 criteria).

A relatively low number of criteria is also

desirable from another standpoint: Already

Galtung (1967) stated that in order to be

applied successfully in practice an index (i.e. a multicriteria

assessment instrument) should be easily understood by the persons

called to assess given phenomena. The instrument should make

immediate sense to the user apart from its mere mathematical

mechanisms. This condition can of course be fulfilled much easier

with a relatively low number of criteria.

ISPI therefore evaluates the inventive step of

inventions on the basis of only four groups of criteria: F

(formalities), P (type of patents), T

(trivial measures), and A (additional indicators)

amounting to a total of 14, or 16 different items (Dolder

2003). The criteria used by ISPI shown in Table

1 reflect a diversity of viewpoints about inventive

step, and the four groups of attributes (F, P, T., A) are as

independent, as can be expected from their common theoretical

starting point, namely the idea that a high inventive step should

yield a high score in all three groups.

In a retrospective series of observations the

statistical correlation between criteria were determined and were

found to be independent to an encouraging extent (see

infra Section 4). In contrast to working with holistic

mechanisms generating one-reason-decisions the rater of ISPI has

to consider criteria which he is prima facie not personally

inclined to take into account and which he would otherwise not

have considered.

It should be noticed that the well balanced

catalogue of ISPI criteria should be applied to a given set of

facts in an exclusive way, and not be extended on a

case-by-case basis by modifications. Any such extension of the

catalogue on a case-by-case basis would harm or un-balance the

instrument and would therefore generate biased results. Such

admission of modifications ad hoc would be harmful for

the conceptual qualities of the system (cf. Katz/Baitsch

2006).

3.2 Scaling qualitative and

semi-quantitative criteria

The majority of the criteria used in ISPI are

qualitative, i.e. can be expressed only in a verbal, or

linguistic way and be answered in a YES-NO, or typical - not

typical way. Therefore, the scaling procedure for the criteria

applied with ISPI had to take into account a majority of

qualitative criteria, such as e.g.

A 43 Was there a long-felt need for the

invention? Were previous attempts not successful?

Applicable YES-NO.

F 4 Was there scientific / technological

competition resulting in the invention ?

Typical - not typical

The different realisations ("values") of

such qualitative attributes are not measured by exact numerical

methods, but are prima facie expressed in verbal patterns. These

verbal patterns have to be subsequently transformed into

numerical scores, which requires that such attributes are

carefully operationalised. In such situations, scales should be

avoided which are too differentiated, e.g. scales from 1 to 10,

since they suggest a (not existing) exact measurement, lead to

undesired compromising and are prone to capture implicit

prejudice, or bias.

Unwarranted / exaggerated fine scales furthermore

suggest the raters to give medium ratings and do not urge the

rater to make real hard decisions and lead to apparently minor

corrections introduced after the assessment has been performed.

The more differentiated the scales are, the more they are

subjected to undesired effects, such as the halo effect, i.e.

scores influenced by the general impression of the object to be

assessed. Therefore to assess qualitative attributes successfully

relatively rough scales should be applied which are able to avoid

the misleading arising from too refined scales (cf. Katz

/ Baitsch 2006).

In view of these difficulties, the scales for the

criteria used in ISPI were conceived as rough as possible, not

suggesting a non-existing objectivity, but requesting real hard

decisions from the raters. In a first step, the scores for the

qualitative criteria are expressed using linguistic patterns such

as high (H), moderate (M) (or: intermediate, medium), and absent

(A), or typical - not typical generating a linguistic set of

values for assessment.

v (H, M, A), or v (T, -T)

In a second step these linguistic values of the

qualitative criteria are transformed in a numerical scale so that

the score obtained for each individual criterion is either

(0-1-2) resulting in a theoretical maximum score of 24 points. A

minority of the criteria are of a semi- quantitative nature:

F3 What was the age of the nearest state of

the art on the application date ?

Less than < 10 years, 10 to 20 years, more

than > 20 years ?

P 21.1 What number of technical specialities

generated the attributes of the invention ?

1 speciality, 2 specialities, or more than

> 2 specialities ?

These (semi)-quantitative criteria of ISPI

assessed by numerical methods were likewise transformed into the

rough score (0-1-2):

F1 Number of the intellectual steps required

to attain the invention starting from the nearest state of the

art: 1, 2 or more >2 ?

The essential point being that one criterion

cannot yield more than a maximum of 2 points indicating a highly

positive contribution to the overall inventive step of

the patent application.

3.3 Attributing weights to individual

criteria

Attributing different weights to the criteria of

a multicriteria instrument can be either implicit, or explicit:

Implicit by attributing different maximum scores to different

criteria, explicit through attributing specific factors of

multiplication to particular criteria.

Attributing different weights to different

criteria in a multicriteria instrument can rarely be justified in

a consistently scientific and rational way. If it is applied, it

is usually based on some pre-formed or inside conceptions of the

value of certain criteria with regard to the overall score of the

phenomena in question. Therefore, it is preferable to apply

neither implicit, nor explicit weighting of the individual

criteria of a multicriteria instrument, but rather to attribute

equal maximum score to each criterion and to abstain from using

different weights for different criteria ( Katz / Baitsch

2006, p. 17-18: "Wissenschaftlich lässt

sich unterschiedliche Gewichtung kaum je begründen").

This corresponds with findings in other fields of decision making

which show that attributing different weights to different

criteria adds little to the accuracy of the results as compared

to attributing equal weight to all criteria (Dawes

1979).

Furthermore, complicated weighting of criteria

can even less be justified in a context full of uncertain

estimates, i.e. in a low-validity environment like inventive

step: Already in 1967 Galtung

(1967: 242 ) warned that multicriteria

instruments should be easily understood by their prospective

users, since otherwise they would not be used at all.

Starting from these general considerations

attribution of weights to the criteria used in ISPI had to take

into account the specific experience of one-reason decisions of

the TBA case law: Due to this one-reason approach the criteria

applied in the case law are always, or at least: usually observed

isolated from other criteria. Furthermore, the criteria are

always found in a winning function, the loosing criteria not even

being explicitly mentioned. Therefore, no consistent ranking, or

different weight of single criteria, or groups of criteria could

be conclusively derived from empirical observations of the past

TBA case law. Since ISPI was conceived in order to replicate past

TBA case law results in a safe way, this basic finding suggested

that each individual criterion should be attributed equal weight

as all other criteria: On the basis of the one-reason approach

observed in past decisions of the TBAs no criteria, or group of

criteria consistently surfaced to generate more decisive power

than other criteria, or groups of criteria. Therefore, in the

context of assessing inventive step under Art. 56 EPC based on

exclusively rational reasoning a consistent attribution of

different weights to different criteria, or groups of criteria

could not be discovered and proposed for further use by the

authors.

3.4 Aggregation / combination

procedure

To be accepted by the relevant practitioners, a

multicriteria instrument should be easily understood by these

practitioners. The instrument should make sense to the user apart

from its mathematical mechanisms (Galtung, 1967,

p. 242 ). ISPI therefore applies the classical procedure of

Simple Additive Weighting (SAW), which is probably the most

widely used MCDA method. In the present context this method of

aggregating has the great advantage to make immediate sense to

users i.e. is easily understood by the non- statistician, legal

or patent practitioners. This linear weighted sum

V(x) = Σ wi vi (xi)

can be realistically assumed to provide a good

overall measure of inventive performance, where xi:

attributes / criteria, wi : weights, and

vi: value functions. As already explained, each value

function vi (xi) assesses the partial

performance of the patent application in attribute xi

in an increasing 0-1-2 scale.

As already mentioned this traditional Simple

Additive Weighting (SAW) of individual scores allows compensation

from one criterion to another: Since the final score obtained by

ISPI is based on summation, the assessed patent application may

compensate poor scores on a particular criterion x1 by

better scores on other criteria xn. Thus, ISPI

functions essentially on a balance-sheet mechanism where positive

and negative performances on different attributes of the assessed

invention are equally considered.

We are aware that even within this balance-sheet

mechanism it is not excluded that particular criteria are

attributed higher (or: lower) scores than they would

realistically merit under the influence of a good (or: bad)

general impression of the assessed patent application This halo

effect can be reduced, but not radically excluded, by selecting

and using independent criteria for assessment ( Thorndike

1920, Rosenzweig 2007, see infra Section

4).

4. Material and Methods

4.1 The test cases:

To avoid particular difficulties of the raters in

understanding the underlying technical facts, both test cases of

our investigation were chosen from the field of (relatively)

trivial mechanical engineering. Two different test cases were

assessed by the participants, one of which resulted in the grant

of a patent, the other in final rejection of the patent

application, both reversed the decision of the first instances

(examination, or opposition division).

Test case A: TBA 176/84 - Pencil sharpener /

Möbius, in re Möbius; Examination division

14.3.84: Application rejected; appeal of the applicant 10.5.84,

decision of the appeal board 3.2.1 on 22.11.85: Patent

granted (technical details: OJ EPO 1986, 50 = Dolder,

2003:124, case 23).

Test case B: TBA 144/85 - Stitching device,

Examination division 13.1.1982: patent granted, two oppositions I

and II, opposition division 9.4.1985 interlocutory decision:

patent upheld in part, board of appeal 25.6.1987: Patent

revoked (technical details: Dolder, 2003:

100, case 21).

In the first test case TBA 176/84 - Pencil

sharpener / Möbius, inventive step was confirmed and a

patent granted on appeal by the applicant. The TBA classified the

application as a transfer, or substitution of elements from one

technical area (sharpening of pencils) to another technical area

(security mechanisms for savings-box slots) The board ruled that

these two specialities were connected only by the general field

of container closing and that the distance between the

two specialities was as large as to confer inventive step to the

surpassing of this distance:

5.3.2 In the present case, even adopting the

same premise as the Examining Division that the person skilled in

the art by abstracting the problem would eventually, in his

search for suggestions as to how he might solve the problem

underlying the application, turn to the broader, that is to say

general field of container closing, while he would then have

entered what the Examining Division considers to be the generic

field, he would not have reached the field of securing mechanisms

for savings-box slots. In view of the technological differences

between the two fields - storage of coins in a container as

opposed to sharpening of pencils with provision for collection of

shavings - there is no reason why it should occur to a skilled

person to refer to this specific area - which the Examining

Division considers to be part of the same broader field - to see

how similar problems had been solved there. (....)

5.3.4 The field of such securing mechanisms

is therefore not one of the neighbouring fields to which a

skilled person concerned with the development of pencil

sharpeners would also refer, should the need arise, in search of

appropriate solutions to his problem.

5.4 In terms of what is therefore the sole

relevant state of the art for pencil sharpeners, the

subject-matter of Claim 1 accordingly involves an inventive step

under Article 56 EPC as has been shown.

In the second test case TBA 144/85 -

Stitching device inventive step was denied by the TBA

and the patent revoked in its entirety. The Board ruled that the

teaching of the application was only a compilation of known

elements resulting in a mere addition of these elements

not achieving any combinatorial (synergistic) effects.

4.7 Therefore claim 1 contains in its

essential part a series of items which are all known in the same

special field to which the general part belongs and make use of

their equally known advantageous properties in their

predetermined way. Although these partial effects contribute to

improve (optimise) the handling of the stitching element, this

does not result - contrary to the allegation of the patentee - in

a combination effect in the sense that a surprising, not

predictable effect representing more than the sum of the

individual effects is achieved. The said items display

exclusively their specific predetermined effect without

influencing each other (....) In a general way, as disclosed by

the patentee, the slider can be brought into the fastening

position without a ramp (ascent piece) - although with increased

manual power. Therefore the ramp (ascent piece) is neither a

condition for the positioning of the ending border (ledge), nor

does it contribute with this ending border (ledge) to a

surprising total effect.

4.8 Based on these findings it can be said

that the object of Claim 1 is obvious to a person skilled in the

art having regard to the state of the art and accordingly does

not involve an inventive step in the sense of art. 56 EPC.

(....)

4.2 Organisation of the investigation

The test case Stitching device was

assessed by seven groups of students involving a total of 188

individual raters, while the test casePencil sharpener

was assessed by nine groups of students involving a total of 201

individual raters. Control group X assessing the test case

Pencil sharpener with unstructured procedures comprised

a total of n = 189 raters.

For practical reasons, university students acted

as raters/assessors, since it would have been impossible to

recruit equally large samples of persons (of n = 200) consisting

of experienced professional raters (i.e. patent examiners and

patent attorneys). Besides this practical reason, it was the

intention of the authors to validate ISPI not only as an

instrument for professionals with long-term experience, but also

to explore its potential as an educational tool for familiarising

students with the difficulties of art. 56 EPC. The prospective

raters (undergraduate students, mainly of engineering and

science) were taught one introductory lesson (45 minutes) on

inventive step as a condition of patentability in which the

different criteria of assessment were outlined and the structure

of ISPI explained. In this introductory lesson students were

given a simple model case which they evaluated in small informal

groups of four to five and/or in informal discussions with their

teachers (Dolder (2003): 79, case 16, T 460/88

of May 21, 1990 - Zentrierring).

In a second lesson (45 minutes) the student

raters were asked to assess the application individually and were

supplied to this purpose with one of the patent applications to

be assessed and the documents of the state of the art as relied

on by the EPO examination sections and appeal boards. In addition

to this, the documentation at the disposal of the raters included

the IPC classification of the patent documents of the cases (for

a preliminary report on the organisation see

Dolder et al. 2011).

The selected criteria for assessment of the test

cases are shown in Table 1 in summary form. The

exact wording of the questions to be answered by the raters were

described in Dolder (2003). ISPI was shortened

for this study to criteria F1 to F5 (formalities), P23.1 to P23.3

(Pencil sharpener), or P21.1 to P21.3 (Stitching device), and A42

to A46 (optional evidence), giving a total of 14 criteria. The

maximum scores obtainable were therefore F1 to F5: 8 points, P21

or P23: 6 points, and A42 to A46: 10 points, i.e. a maximum score

of 24 points.

5. Results

5.1 Independence of criteria

From a theoretical standpoint inter-criteria, or:

inter-item correlation, i.e. interdependence of criteria of a

multicriteria instrument should be modest and not statistically

significant. This is necessary in order to control and reduce

artefacts caused by (a) invisible or disguised redundancies of

individual criteria and (b) halo effects which could

both contribute to exaggerate positive ratings of those objects,

which were viewed by the raters in an overall "positive"

light (Thorndike 1920, Rosenzweig 2007, Bechger et

al. 2010).

To test the criteria used in ISPI the inter-item

(inter-criteria) correlation (Pearson) and rank correlation

(Spearman) between the scores generated by pairs of criteria were

calculated. Since the scores achieved in individual criteria were

not likely to be normally distributed, we preferred to use

nonparametric rank correlation (Spearman) which are independent

of a specific distribution pattern. As expected, the values found

for inter-criteria correlation within their groups

(intra-group, i.e. F, P,T,and A) were slightly lower as compared

with the inter-group correlation. This difference is probably due

to aggregating effects within the groups of criteria.

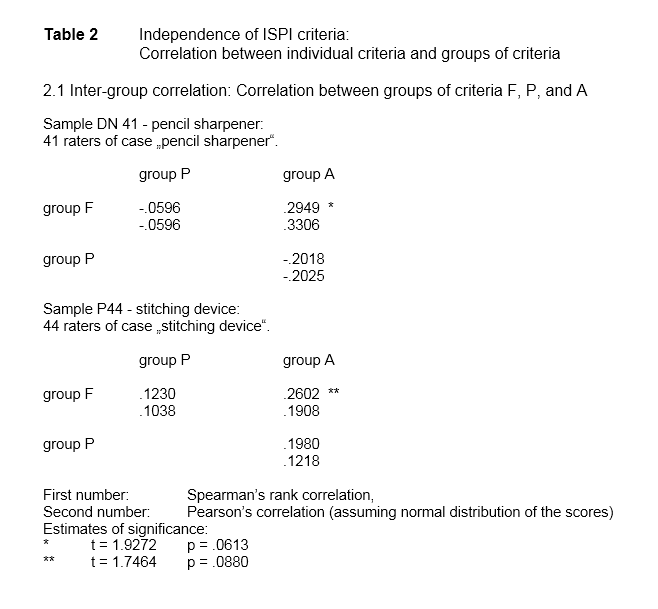

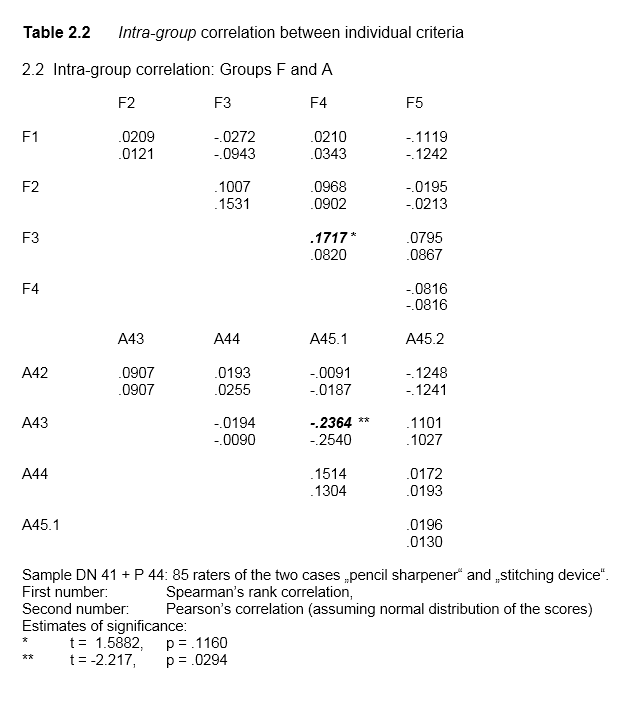

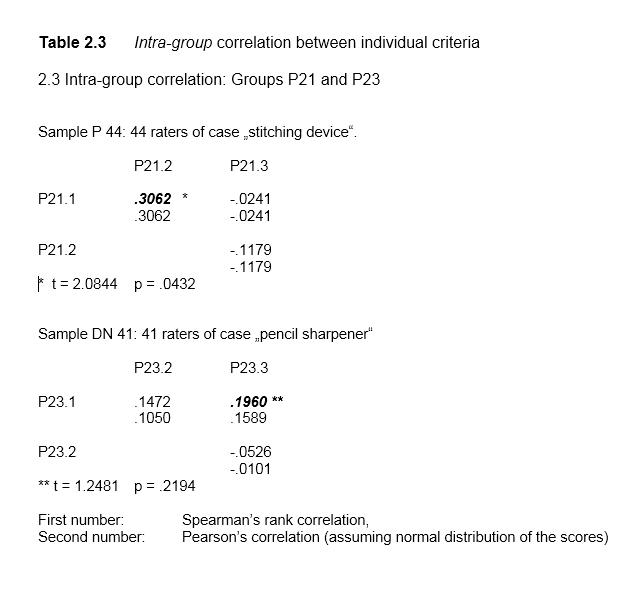

While inter-group rank correlation varied from

Rs= -.0596 to .2949 in the pencil sharpener sample (41 raters),

they varied from Rs = .1230 to .2602 in the stitching device

sample (44 raters). (Table 2.1). In contrast to

these findings intra-group rank correlation based on a sample of

85 raters in the two test cases (41 raters, case pencil sharpener

and 44 raters, case stitching device) varied from Rs = -.0195 to

.1717 (F group) and from Rs = -.0091 to -.2364 (A group),

intra-group correlation within the two P groups (P21 and P23)

varied from Rs = -.0241 to .3062 (group P 21, 44 raters, case

stitching device) and from Rs = -.0526 to .1960 (group P23, 41

raters, pencil sharpener). (Table 2.2 and Table 2.3).

Additional evidence for an only modest

interdependence in content between the criteria was found by

calculating the rank correlation Rs between any two criteria of a

sample of n = 59 raters of the pencil sharpener test case. Of a

total of 91 possible Spearman Rs correlation between any two

criteria of this data matrix only 8 (8.8%) attained values

higher than Rs = +/-(0.3000) and critical values of t

> 2.00 at the .05 level of significance (two-tailed test). Of

these 8 values only 6 were significant at the .01 level (t >

2.660, two-tailed test).

H.R. Arkes et al.

(2010, 253) staged their empirical investigation of the merits of

holistic and disaggregated judgements on seven criteria for 60

randomly selected colleges and universities and determined the

absolute value of the largest correlation between any two

criteria (characteristics) to be .20, which was not significant

(p > .10). Therefore the seven criteria "were deemed to

be orthogonal", and therefore held acceptable for experimental

use.

Katz / Baitsch (2006)

reported correlation for their ABAKABA index for assessing

working place requirements with maximum values for inter-group

correlation (Pearson's) of .62 and for intra-group correlation

.73. These maximum values were considered to by sufficient for

assuming independence of the criteria and for practical use of

the ABAKABA index ( "als durchwegs gering bezeichnet

werden"; "zeugen aber dennoch von einer ausreichenden

Unabhängigkeit auch der Einzelmerkmale").

The observed minute inter-criteria correlation

found with ISPI index compare advantageously with the correlation

found in these previous reports on multicriteria instruments. The

criteria used in our investigation were therefore considered to

have an acceptable degree of independence from each other and as

a practical result were deemed to be sufficient, adequate and

suitable for practical use of index ISPI in assessing inventive

step in patent applications and potential inventions.

5.2 Inter-rater

reproducibility

5.2.1 The instruments

The patent practitioner using ISPI is mainly

interested in whether or not the scores obtained with ISPI are

accurately reproduced from one individual rater to another. This

inter-rater reproducibility of results, representing one aspect

of the reliability of the index, can be assessed on the

basis of the statistical concordance between the scores

obtained by different raters (inter-rater concordance). This

concordance is usually measured by Cronbach's Alpha

taking into account the ratings obtained from every individual

rater for every individual item (criterion), thus

establishing a two-dimensional matrix of results. In order to

avoid unwarranted assumptions, the nonparametric rank correlation

of Spearman were again applied as the basis of the

calculations. This was necessary, since a normal distribution of

the scores could not be expected ( Cronbach

1951, see supra 2.2).

Cronbach's Alpha is usually applied to

measure inter-criteria concordance, but can also be used

to measure inter-rater concordance (Cortina

1993). A relatively high inter-rater

concordance (a > 0.7) is desirable to indicate sufficient

reproducibility of the results of a multicriteria test

procedure.

5.2.2 Inter-rater alpha observed

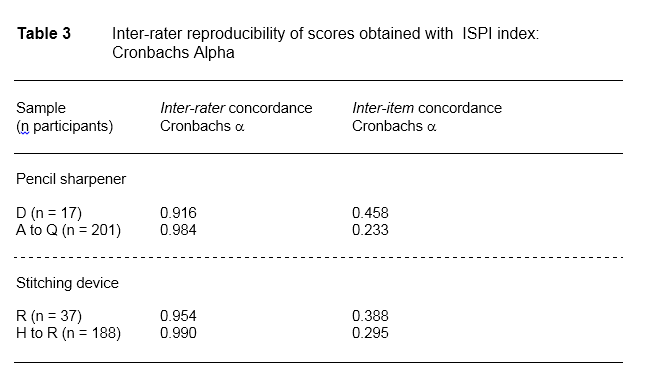

As expected, we found high values (a > 0.9)

for inter-rater concordances by Cronbachs Alpha

(Table 3). As could also be expected, the values

of Cronbachs Alpha increase slightly with the number of

raters: Smaller samples (n < 40) resulted in values below

0.95, while both over-all samples of about n = 200

raters each attained a value of around 0.99. (cf. Cortina

1993, 103) It should be noticed that in the context of

ISPI relatively small samples of raters with n < 40 seem to be

sufficient to obtain a value of inter-rater alpha sufficient and

suitable for all practical purposes.

5.2.3 Critical Ratio q < 0.5

It should be considered that the set of facts in

both test cases were mis-classified once by their respective

examination boards before they were re-classified correctly by

the TBAs. Both test cases can therefore be considered as

borderline cases and therefore as comparatively difficult tasks

for assessment. In the light of this constellation of facts the

observed highly significant inter-rater reproducibility of the

ISPI scores could not be expected prima facie.

Therefore, the reliability of the index, as established on this

set of test cases, can be considered to be satisfactory for

practical purposes and ISPI can be expected to improve

inter-rater reproducibility in the assessment of

inventive step significantly as contrasted to non-structured

holistic procedures.

Based on these findings it is suggested that a

multicriteria index used for legal decision making should have a

ratio q of inter-item and inter-rater concordance (expressed as

Cronbach's Alpha) not exceeding q < 0.5:

q = a (inter-item) / a (inter-rater) <

0.5.

5.3 Distinctive power

5.3.1 Multicriteria vs. one-reason heuristics

The patent practitioner assessing inventive

quality with ISPI is furthermore interested whether this method

is capable to distinguish between two inventions with regard to

inventive step which he could not safely distinguish with

unstructured procedures. In other words, he is interested to what

extent ISPI is capable to safely detect differences of

inventive step bet-ween inventions which he could not safely

detect by unstructured procedures, like the one-reason decisions

quoted earlier (see supra Section 1).

In the present study this aspect was obviously

important since both test cases were borderline cases located

near the borderline between presence & absence of inventive

step and could obviously not be distinguished safely by

unstructured procedures. This latter finding is

evidenced by the fact that each test case had been mis-classified

in the first decision by the respective examination divisions and

the result subsequently reversed by the TBA.

The distinctive power of a diagnostic instrument

like ISPI can be assessed by a number of statistical tests which

decide whether under a pre-determined level of significance a

difference existing in a population is evidenced also as a

difference between two samples drawn from this population. They

answer the hypothesised question (Ho) whether the

observed independent samples (e.g. frequency distributions) have

been drawn from the same population (or from populations with the

same distribution) and can therefore be consistently

distinguished by the diagnostic method applied.

5.3.2 Comparing mean values

In a first step the distinctive power of ISPI was

evaluated by comparing the mean values by the t-test assuming

that the ISPI ratings of the two test cases had unequal variances

and represented normal distributions which is a reasonable

assumption for large samples of raters as used in our

investigation.

Example # 1: Large number of raters n = 201

and n = 188

Ho: Hypothesised mean difference

is 0

Pencil sharpener Stitching device

Total n 201 188

Mean 8.33 5.95

SD 2.44 2.59

degrees of freedom n = 381

test statistics t = 9.3136

critical values of t: 2.5888 (two-tailed) ,

2.3362 (one-tailed) , p = .99

1.9662 (two-tailed), 1.6489 (one-tailed), p =

.95

Therefore H0 is rejected at both

levels of significance.

Given the observed standard deviations (SD) the

frequency distributions of the scores in the two test cases

showed a considerable area of overlap in small and large samples.

However, based on the relatively large number of raters involved

the results of the t-test comparing means were significant at

both the 0.01 and the 0.05 level. It can be inferred therefore

that ISPI had in fact the capacity to distinguish the two patent

applications with regard to inventive step in a significant and

safe way. In contrast to the fact that both inventions had been

mis-classified once by their competent boards of examination and

could therefore be considered not to be safely

distinguished by unstructured holistic procedures.

5.3.3 Comparing frequency distributions

The Kolmogorov - Smirnov two-sample test answers

the practical question whether the cumulative frequency

distributions observed in two independent samples can be

distinguished assuming a predetermined level of significance. In

contrast to the t-test (for comparison of mean values) this test

offers the advantage that it does not require the population(s)

from which the samples were drawn to be normal distribution(s),

but only that the variable under study is continuous

(Smirnov 1948, Siegel 1956).

Therefore, the cumulative frequency distributions

of the ISPI scores observed in the two test cases Pencil

sharpener and Stitching device were calculated for

different numbers of raters and the significance of the

differences D between the two distributions was evaluated with

the Kolmogorov-Smirnov two sample test.

Example # 2

Hypothesis Ho: The two

observed cumulative frequency distributions are identical, i.e.

they are drawn from the identical population.

Values of the frequency distribution 0 ≤

xi ≤ 15

Test case: Pencil Sharpener Number of raters

n1 = 201

Observed: Mean 8.33, SD 2.44

Test case: Stitching part Number of raters

n2 = 188

Observed: Mean 5.95, SD 2.59

Two-sample test of

Kolmogorov-Smirnov (see Siegel, p. 128, formula 6.10a):

Value observed D = maximum [Sn1 (X) -

Sn2(X)] = 0.3785

p < 10 -4 (one sided) p < 10

-4 (two sided)

Levels of significance of D, if n1 =

201, n2 = 188

D = F .SQRT [( n1 + n2) /

n1 . n2] = F. SQRT [( 188 + 201) / 188 .

201] = F . 0.1015

1 - α = 0.95 (5 %) : F = 1.36, hence D = .1380

1 - α = 0.99 (1 %) : F = 1.63, hence D = .1654

The maximum difference D between the cumulative

frequency distributions observed in the two test cases by large

numbers of raters (Example # 2 n 1 = 201,

n2 = 188) was equally significant at both the 0.95 (F

= 1.36) and the 0.99 level of significance (F = 1.63), while the

exact value for p was found to be less than p <

10-4. Hence, it is extremely unlikely that the two

cumulative frequency distributions observed in example #2 were

drawn from the same population. And therefore, hypothesis

Ho could again be safely rejected.

Although the two assessed inventions have a

similar case history, and although the mean values of the

frequency distributions generated by a large number of raters

(Example # 2) are similar (Pencil sharpener mean = 8.33;

Stitching device mean = 5.95) and the corresponding standard

deviations (SD) are practically identical, applying ISPI to these

two inventions results in a statistically significant distinction

between the two test cases.

5.4 Selecting a Reference Cut-off Value

5.4.1 Cut-off values in legal decision making

When evaluating a set of facts described by some

criteria, there are different kinds of analyses that can be

performed in order to provide support to decision-makers.

Alternative facts can be arranged in a rankordering allowing to

identify the best and the worst alternative; or the alternative

facts can be classified or sorted into predefined groups. While

rankordering and selecting the best are based on comparative

judgements and depend on the considered group of alternatives,

the decision-maker applies abstract and predefined reference

points for making classification & sorting decisions (

Roy, 1985, Zopounidis et al.,

2002).

In legal decision making, the ratings obtained

through multicriteria procedures can be used either for comparing

and ranking a given set of facts within a group of similar

phenomena. Example: Selecting the highest ranking alternative

from a group of alternatives, e.g. selecting the best offer

within a group of offers from different contractors in public

procurement.

On the other hand, the ratings obtained through

multicriteria procedures can be applied as a tool for

classification and decision making of phenomena without direct

comparison within a group of alternatives. In this situation a

criteria aggregation model based on absolute judgements is used,

which provides a rule for the classification of the alternatives

on the basis of reference points (cut-off points) that

distinguish the classes (Gaganis et al.

2006). To perform this task, the total scores of the

phenomena under assessment are compared with a reference cut-off

threshold which is either met or failed. This reference cut-off

threshold can be selected inter alia on the basis of

past experience, if continuation of this past experience is

desired - as is usually the case in legal decision making.

Example: Decision on early remission of individual offenders in

criminal law based on an assessment of the immanent risk of

recidivism (König 2010).

5.4.2 ISPI: From past experience to consistent

cut-off values:

The function of ISPI consists in classifying

patent applications into two classes which satisfy or fail the

statutory requirement of inventive step (EPC Art. 56). The normal

approach to address such classification problems is to develop a

rule for the classification of the alternatives with one (or

more) reference cut-off point(s) which distinguish the classes.

(Gaganis et al. 2006, 107/108). Starting from

the basic consensus to achieve replication of past decision

experience and past decision standards the classification rule

with its cut-off threshold t0 can be selected so that

the pre-existing classification of applications provided by past

experience can be replicated as accurately as possible. The basis

of the classification is thus not a ranking or comparison within

an existing group of results (scores), but a comparison of a

given result (score) with past experience. Based on the ISPI

scores of the patent applications as defined by the value

function V(xi), their classification into two groups

C1 (+) and C2 (-) can be performed in a straightforward way

through the introduction of one cut-off threshold t0

such that

V(xi) ≥ t0 «

application belongs to group C1 « inventive step (YES)

V(xi) < t0 «

application belongs to group C2 « inventive step (NO)

Therefore, in the context of validating ISPI

minimising the rate of mis-classifications (as compared to the

results of the two template cases, i.e. on past case law) was the

obvious approach for determining this cut-off point

t0. A mis-classification consisted in a deviation from

past decision standards, i.e. non-compliance with the

classification rule t0. Based on this common consensus

(assumption, i.e. continuation and replication of the standards

of past case law), the reference cut-off threshold t0

could be selected empirically: The two test cases decided in the

past (pencil sharpener, stitching device) which resulted in

opposite decisions (grant - rejection of grant) were assessed by

a number of independent raters and the two frequency

distributions of the ratings were determined. Of each ISPI rating

generated by an individual rater it was known whether it was

classified in the past by the TBA as inventive C1 (pencil

sharpener), or non-inventive C2 (stitching device). Applying the

theory of diagnostic tests (Armitage et al.

2002) to these findings an empirically consistent

cut-off value t0 could be selected, which complied

with the standards of past decisions of the TBAs of EPO.

5.4.3 Minimising mis-classification through the

approach of the ideal observer

Since minimising the rate of mis-classifications

(as compared to the results of the two test cases A and B, i.e.

on past case law) was the obvious approach for determining the

cut-off point t0, the rate of mis-classifications

violating the rule of t0 was observed and minimised by

selecting the cut-off point through the approach of the ideal

observer. Total mis-classification error represents the

sum of the rate of false positive (fp) and the rate of false

negative (fn) results depending on the particular cut-off point

t0. The criterion is based on the assumption that

false positive results (fp, &alpha-errors) and false negative results

(fn, &beta-errors) in the assessment are equally important from a

practical point of view.

This assumption is justified in the present

context for two reasons: ISPI is based on the implicit community

consensus that the standards for evaluating inventive step

applied in the past should be continued and maintained in the

future. Thus, mis-classifications in both directions are equally

undesired from the viewpoint of continuation. The second reason

for assuming equal importance to both types of

mis-classifications is based on the empirical observation that

the percentage of granted and failed patent applications in

European patent prosecution is approximately equal and nearly

constant in the long-term, i.e. about equal percentages of grants

as compared with rejections and withdrawals of patent

applications and revocations of patents granted (EPO

2009). Therefore, the frequency of mis- classifications

can also be expected to be similar in both directions.

The approach of the ideal observer based on

minimising total mis-classification offers a consistent cut-off

point for continuation of the standards of past decision-making.

Through this procedure a cut-off point is chosen by relying on

the standards of past experience and applying this cut-off point

to future cases means to assess new cases by the standards of

past decisions.

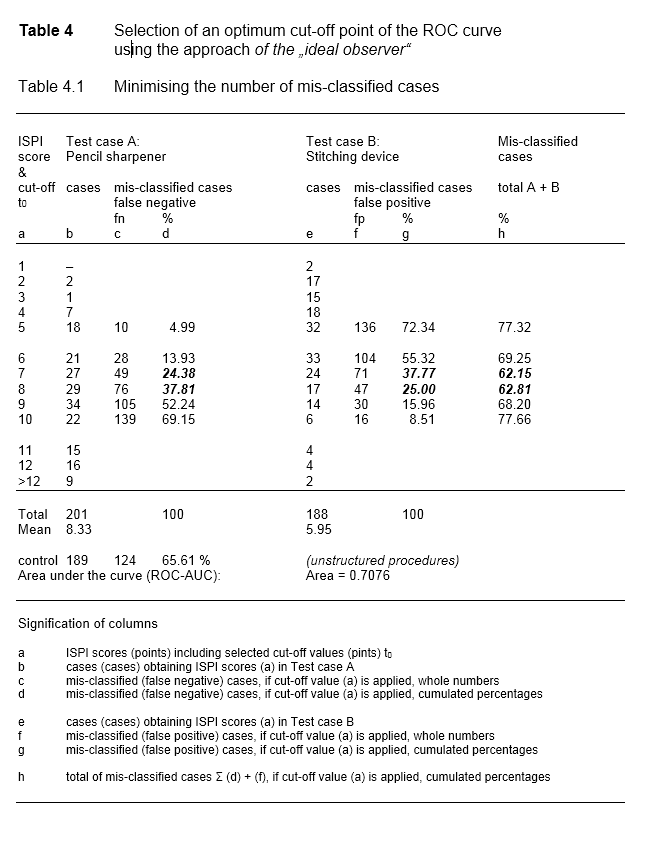

Table 4.1 shows the frequency of

false negative (fn) decisions (b-errors: test case A pencil

sharpener) and of false positive (fp) decisions (a-errors: test

case B stitching device) in relation to various cut-off points

chosen under the rule of the ideal observer. If a cut-off value

of t0 = 7 is applied, 49 (24.13 %) false negative

decisions are observed in the pencil sharpener case, while 71

(37.76 %) false positive decisions are found in the stitching

device case. If however a cut-off threshold of t0 = 8

is applied, the quota of false negative decisions is found to be

76 (37.44 %) of a total of 201 ratings in test case A (pencil

sharpener), while the quota of false positive decisions in the

test case B (stitching device) is 47 (25 %) of a total of 188

ratings. Therefore the two cut-off values t0 = 7, or

t0 = 8 ISPI points are virtually equivalent with

regard to complying with the ideal observer 's rule of minimising

mis- classifications. Following this line of reasoning a cut-off

threshold of t0 = 8, is suggested as a consistent

value for future use of ISPI, since a slightly smaller rate of

false negative decisions (t0 = 8) is preferred.

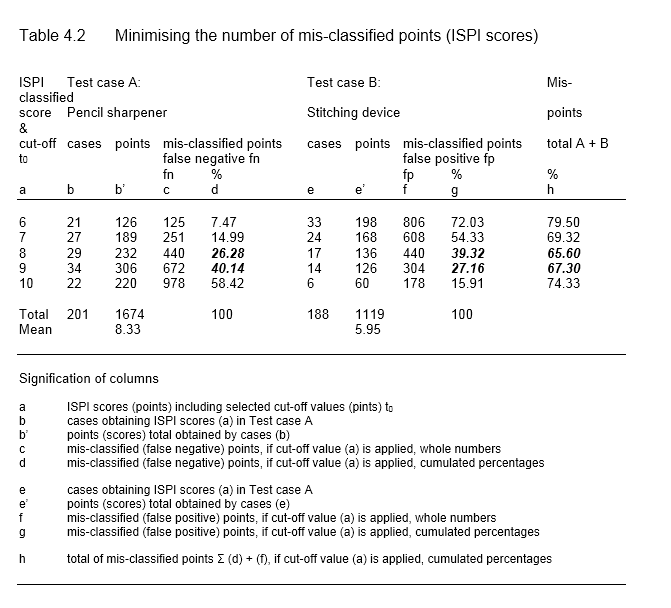

Almost identical cut-off values t0 are

obtained if points (scores) instead of individual decisions

(results) are used for minimising mis-classification

(Table 4.2): Taking the magnitude of the

mis-classified scores into account should therefore not change,

or influence the choice of the consistent cut-off point to a

significant extent.

The rate of correct/false decisions generated by

applying ISPI was compared to the rate of correct/false decisions

observed, when unstructured holistic procedures were applied on

the same test case. In the pencil sharpener test case A

the control group X (189 raters) generated only 65 (34.39 %)

correct classifications, while the raters (n1 = 201)

using ISPI would have produced 62.19 % correct

decisions, if a cut-off point of t 0 = 8 was applied.

Therefore, within the limited context of our study the

multicriteria decisions were clearly superior to the holistic

decisions with regard to avoiding mis-classifications. This

finding is in keeping with the research of Gaganis

(2006) on assessing the financial soundness of banks and

Arkes et al. (2006) on the evaluation

of scientific presentations.

Furthermore, the results of Table 4.1

/ 4.2 and the classifications obtained

by the students with ISPI (i.e. 62.19 % correct classifications

in the first round) seem to point to the fact that the expertise

contained in IPSI does not only help teaching this essential

point of patent law, but that ISPI can enable students to achieve

valid assessments of inventive step.

5.4.4 Area under the ROC-curve (ROC-AUC)

Minimising errors by the approach of the ideal

observer corresponds to the choice of an optimum operating point

in a ROC curve (receiver operating characteristic curve).It

remains controversial to what extent the observed area under the

ROC-curve (ROC-AUC) can be considered a quality measure of

multicriteria instruments. AUC values of .60 have been qualified

as not sufficient, while values of .80 were considered to be

satisfactory and of .90 to be high (Andrej König

2010). In a different context, a ROC-AUC value of .75

was considered high and indicating that the effect measured was a

large size effect (Dolan and Doyle 2000).

However, the capacity of ROC-AUC as an instrument to measure the

quality of multicriteria instruments is restricted by the fact

that the value of ROC-AUC varies according to the size of the

effect measured with a particular multicriteria index. Therefore,

this parameter can be safely applied for quality measurement of

multicriteria instruments only, if the identical set of facts is

assessed using a number of different multicriteria instruments

and the obtained results from these instruments are subsequently

compared.

Under these not yet definitely established

theoretical foundations it remains open to discussion which

inferences can be drawn from our finding that the area under the

ROC-AUC of ISPI was calculated to be .7076 for the selected

optimum cut-off value of t0 = 8 (Table

4.1).

It is equally controversial to what extent the

observed values of ROC-AUCs are influenced, or falsified by the

so called base rate fallacy (Maya Bar-Hillel 1980, D.

Kahnemann / P. Slovic / A. Tversky 1982, König 2010,

69-71). However, this effect on ROC-AUC can be

neglected, if the long-term base rate is approximately R = 1.

This value is achieved in European patent prosecution, since the

number of granted and failed patent applications in the EPO is

nearly equal and constant in the long-term perspective: about

equal percentages of grants as confronted to rejections and

withdrawals of patent applications and revocations of patents

granted (EPO 2009). Therefore, the effect of

base rate fallacy should not be critical for assessing inventive

step with ISPI.

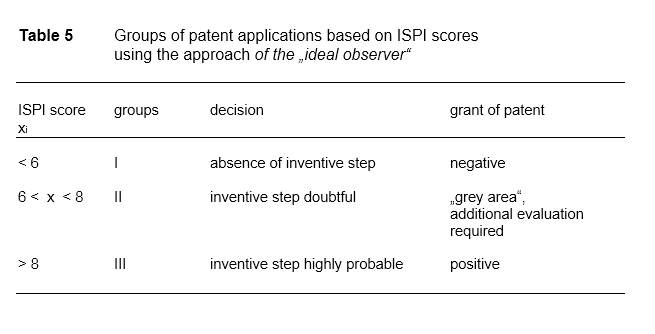

6. Formation of groups of patent applications

Patent applications can be classified into more

than two groups C1, C2, ....Ci

on the basis of their ISPI scores introducing more than one

cut-off points ti. (for group formation in different

contexts of multicriteria analysis see Gaganis

(2006) and Jessop (2001).

In a first attempt for group formation the mean

values of 5.95 and 8.33 obtained in the two test cases A and B

respectively generated reference points for classifying ISPI

scores (i.e. patent applications) into three groups

(Table 5). Applications with ISPI scores

xi £ 6 (group I, mean xi = 5,95)

would indicate a highly probable lack of inventive step,

applications with ISPI ratings xi ≥ 8 (group III,

mean xi = 8.33) would be relatively safe indicators of

positive inventive step, while applications with ISPI ratings in

a grey area between 6 < xi < 8 (group II) should

be further examined to decide definitely on inventive step.

The selection of the boundaries of the grey area

is obvious: Since inventive step is (at least implicitly) based

on the perception of more than average performance, it would seem

reasonable that ISPI scores higher than the mean value in a case

found to be inventive by the court in the past (test case A)

could safely be qualified to be inventive. It would seem equally

indicated that ISPI scores lower than the mean score of a case

found to be non- inventive (test case B) could be qualified

safely to be non-inventive.

An alternative approach to generate multiple

cut-off points ti. could follow the standard procedure

of the first round of Delphi assessments to sort out values by

means of the quartile values of their respective frequency

distribution (Sackmann (1974): 45 - 49, Scheibe et al.

1975: 277, Kern, W. / H.-H. Schröder, 1977:

152/153).In our sample of test cases A and B the upper

limit of the third quartile (Q3) of the scores of test case A

would form the upper boundary (xi = 9.545), while the

value of the first quartile (Q1) of the data of test case B

(xi = 3.722) would form the lower boundary of the grey

area.

This classification of patent applications into

three different groups based on multicriteria scores corresponds

with a classification of cases into three categories with regard

to conforming with statutory terms as proposed by Koch /

Rüssmann (1982): 194 based on normative reasoning (Drei-Bereiche-Modell:). A first group

of cases complying safely with the requirements of the statute

(positive candidates), a second group missing the requirement

(negative candidates), and a third intermediary group (neutral

candidates) which cannot be assigned in a first round safely to

either group and should therefore be evaluated with additional

procedures

7. Discussion

The present study was performed in order to

validate empirically the properties of ISPI as an instrument for

improving reliability (reproducibility) in assessing inventive

step of patent applications as compared to one-reason decision

making. As expected, the features of ISPI which were studied

proved to be efficient for performing their functions:

Independence of the applied criteria, inter-rater reproducibility

of results, and distinctive power.

The essential advantage of assessing inventive

step by ISPI as compared to unstructured holistic methods, may be

found in the consistent constraint for completeness and

standardisation exerted on the decision-maker. This constraint

towards completeness requires the rater to assess a relatively

large number of relevant criteria and should prevent him from

taking one-reason decisions using one single criterion of

reasoning.

The multicriteria instrument ISPI can improve

reliability (reproducibility) in assessing inventive step, but

will not eliminate all controversies in legal decision making

related to this topic. However, the remaining controversies

should be considerably reduced in number and limited in scope to

a small number of critical issues in a specific case. This could

improve the quality management of decisions on inventive step as

compared to controversies related to inventive step arising from

unstructured holistic procedures, i.e. one-reason decisions.

The present investigation could be extended in

various directions, such as introducing different

technology-specific criteria into ISPI reflecting the special

technological environment in different scientific specialities.

Furthermore it is obvious that ISPI could not only be used in

legal decision making arising in patent prosecution and patent

litigation, but also in valuing patent assets for financial

transactions. In our opinion, the potential of multicriteria

instruments for legal decision making has not been adequately

recognised so far. It has not escaped our attention that in a

number of other legal areas containing difficult statutory

expressions multicriteria analysis could find additional

applications and improve the accuracy and reproducibility of

decisions.

References

The authors gratefully acknowledge valuable

advice from two reviewers in the course of peer review of the

paper.

Arkes HR / Claudia Gonzalez-Vallejo, Aaron J.

Bonham, Yi-Han Kung, Nathan Bailey 2010, Assessing the merits and

faults of Holistic and Disaggregated Judgments, Journal of

Behavioral Decision Making 23: 250-270.

Arkes HR, Victoria A. Shaffer, Robyn M. Dawes

2006, Comparing holistic and disaggregated ratings in the

evaluation of scientific presentations, Journal of Behavioral

Decision Making 19: 429-439.

Armitage P. / G. Berry / J.N.S. Matthews 2002,

Statistical Methods in Medical Re-

search , 4th ed. Oxford etc., p.

697.

Bar-Hillel M. 1980, The base-rate fallacy in

probability judgments, Acta Psychologica

44 (), 211-233.

Bechger TM., Gunter Maris, and Ya Ping Hsiao

2010, Detecting halo effects in performance-based examinations,

Applied Psychological Measurement 34,

607- 619

Bryant, Chris, 1997, Stafford Cripps, The first

modern Chancellor, London 1997, 60-62.

Büttner J. 1993, in: Evaluation Methods

in Laboratory Medicine (ed. R. Haeckel), Weinheim etc., p.

27 f.

Cortina JM. 1993, What is coefficient Alpha ?

Journal of Applied Psychology 78, 98-104.

Cronbach LJ. 1951, Coefficient Alpha and the

internal structure of tests, Psychometrika 16, 297 -

334;

Dawes R.M. 1979, The robust beauty of improper

linear models in decision making. American Psychologist

34 , 571-82

Dolan M., M. Doyle 2000, Violence risk

prediction, British Journal of Psychiatry

177, 303-311, 304/5.

Dolder F. 2003, Erfindungshöhe,

Köln etc. 2003, Catalogue of criteria: pp. 332. application

of the Delphi technique in assessing non-obviousness of patent

applications: p. 339.

Dolder F., Ann Ch., Buser M. 2011, Beurteilung

der Erfindungshöhe mit Hilfe eines additiven multi-item

Indexes, GRUR 113, 177- 183

Duhigg C / Steve Lohr 2012, An arms race of

patents, NYT International Weekly, 15. October 2012, ,

page 4.

European Patent Office 1986, Test cases: Case

pencil sharpener: EP 031 470 (Pencil sharpener), T 176/84 -

pencil sharpener / Möbius OJ EPO 1986, 50 = GRUR Int. 1986,

265 = Dolder, ibid. case 23, p. 124.; State of the art: DE-C- 1

003 093 (pencil sharpener), DE-A- 2 513 051 (pencil sharpener),

DE-C- 1 960 978 (securing mechanism for savings-box slots);

Case stitching device: EP 011 819 (stitching

device). T 144/85 - stitching device = Dolder, ibid. case 21, p.

100 - 112.state of the art: GB-A-1 417 580, DE-U-7 118 031.

European Patent Office 2009, Annual

Report, lists 134'542 applications filed (Euro and

Euro-PCT), 102'178 European examinations and 51'696 patents

granted in 2009 (p. 62/63). Cases settled by TBAs in 2009: 1918,

allowed (in part) 740 (38.6 %), dismissed 589,

otherwise (e.g. withdrawal) 589; based on opposition procedures

(inter-partes): cases settled 1116, allowed (in part) 508

(45.5 %), dismissed 337, other 271 (page 41).

Opposition procedures: Patent revoked 43.6 %,

patent maintained in amended form 30.1 %, opposition rejected

26.3 % (page 19).

Gaganis Ch., F. Pasiouras and C. Zopounidis 2006,

A MCD Framework for measuring banks' soundness around the world,

Journal of MCDA 14, 103-111.

Galtung, Johan, 1967, Theory and methods of

social research, Oslo 1967, p. 242.

Gigerenzer G. 2007, Bauchentscheidungen,

München 2007, 13 ff.

Jessop A. 2001, Multiple attribute probabilistic

assessment of the performance of some airlines, in: M.

Köksalan, S. Zionts, Multiple criteria decision making

in the new millenium, Lecture Notes in Economics and Mathematical

Systems, Vol. 507, Berlin etc.: Springer 2001, 417-426.

Kahnemann D. / P. Slovic/ A. Tversky 1982,

Judgement under uncertainty: Heuristics and biases,

Cambridge 1982, p. 153-160.

Katz, Christian P., Christof Baitsch, Arbeit

bewerten - Personal beurteilen, Zurich 2006:

"Wissenschaftlich lässt sich unterschiedliche

Gewichtung kaum je begründen" (p. 18).

Kern, W. / H.-H. Schröder, 1977, Forschung

und Entwicklung in der Unternehmung, Reinbek 1977, p. 152

/153.

Koch H-J / Helmut Rüssmann 1982 ,

Juristische Begründungslehre, München 1982,

pp. 194- 201

König A. 2010 Der Nutzen standardisierter

Risikoprognoseinstrumente für Einzelfallentscheidungen in

der forensischen Praxis. Recht & Psychiatrie

28: 67-73, 68.

Ravinder H.V. 1992, Random error in holistic

evaluations and additive decompositions of multiattribute utility

- An empirical comparison, Journal of Behavioral Decision

Making 5: 155-167.

Ravinder H.V., Don N. Kleinmuntz 1991, Random

error in additive decomposition of multiattribute utility,

Journal of Behavioral Decision Making

4: 83-97 (1991).

Rieskamp J. / U. Hoffrage 1999, When do people

use simple heuristics, and how can we tell ? in: G. Gigerenzer /

P.M. Todd, Simple heuristics that make us smart, New

York/Oxford 1999, p. 141 ff.

Rosenzweig, P. 2007, The halo effect,

New York etc. 2007

Roy, B., 1985. Méthodologie

Multicritère d'Aide à la Décision.

Economica, Paris.

Sackmann, H., Delphi Assessment: Expert opinion,

forecasting, and group process, RAND Santa Monica 1974

(R-1283-PR).

Scheibe M. / Skutsch, M. / Schofer, J. 1975,

Experiments in Delphi methodology. In: Linstone, H.A., Turoff, M.

(eds.): The Delphi Method: Techniques and Applications.

Addison-Wesley, Mass. 1975.

Siegel S. 1956, Nonparametric statistics for

the behavioral sciences, New York etc. 1956: McGraw-Hill, p.

127- 136.